Before the Break-Fast

A New Scroll of LA Jewish News

Folks,

This is my appeal: At the New Year, I hope you are ready once again to support MegilLA. If you have been reading for free, it’s time for a change. With each issue, I work to bring you a fresh perspective on the Jewish life around us, and I need your financial support to continue for another year. Please become a PAID SUBSCRIBER today.

G'mar chatimah tovah

A good final sealing in the Book of Life

Edmon J. Rodman

////\/\\\\

////\/\\\\

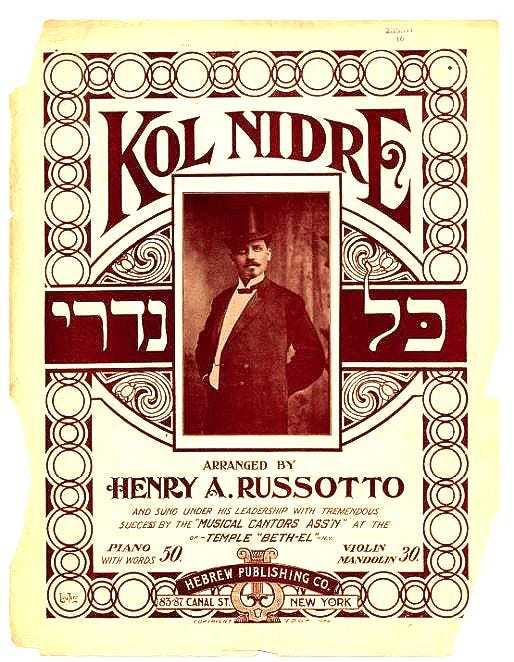

The call of Kol Nidre

New York : Hebrew Publishing Company, 1907, Library of Congress

Edmon J. Rodman

Although you are not sure why, you don’t want to be late for Kol Nidre. As the sun is going down, there you are in the car, even running a yellow light or two, hurrying toward the shul, temple, Jewish center, or wherever it is you go to begin Yom Kippur.

It’s not as if you’re that religious, but somewhere in your head, where yontif memories are filtered into expectations, and doubt rubs up against belief, the majestic music and solemn words — of which you know only a few — are calling: Kol Nidre, ve-esarei, va-haramei, v’konamei.

As you look for parking, you wonder where these feelings are coming from. Is it that Kol Nidre is a powerful prayer or blessing? It’s neither. Kol Nidre, which means “all vows,” is a legal formula for the annulment of “vows, renunciations, bans, oaths, formulas of obligation, pledges and promises,” made not to another, but to yourself and God.

The murky origins of Kol Nidre do not provide much of an explanation for why it has had such a lasting grip on us. Although in Spain it might have relieved some Marrano Jews of guilt from the vows they took upon being forced to convert, many researchers believe the legal formula already was in existence long before that, sometime in the eighth or ninth centuries. The tradition of saying Kol Nidre also is supported by a Talmudic statement that calls for a similar practice to nullify every vow.

Whatever its origins, according to “A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice” by Isaac Klein, the purpose of Kol Nidre has been “to provide release from vows in matters relating to ritual, custom and personal conduct, from inadvertent vows; and from vows one might have made to himself and then forgotten. It does not refer to vows and promises to other people.”

Yet, throughout the formula’s history, that has not been the universal understanding. During the Middle Ages in Europe, for instance, some Christian courts and monarchs held that it meant a Jew could annul any promise. Some mid-19th century Reform rabbis, recognizing the confusion it could cause, even tried to do away with the legal formula.

Written in Aramaic, the language in which most Jews were conversant at that time, the idea was that everybody should understand it. Connecting us over the centuries to that age is the Jewish perspective that words are important, and that at times a promise made to ourselves or God was not made thoughtfully, realistically, with enough knowledge or the right intent, and we need a way to start anew. Kol Nidre presents that rare opportunity to reset, and perhaps it is this opportunity that draws us to hear it year after year.

Adding to its place in our lives, during the Ten Days of Repentance, the period of time from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur, there is an opportunity to resolve issues between you and other people, but during Kol Nidre, there is an opening to resolve issues of the self and your relationship with God.

Helping to add drama to the recitation of this legal formula is the setting. Standing before the heavenly court of life and death brought to mind by the Yom Kippur liturgy, the recitation of Kol Nidre is the time to deliberate on our vows. The tradition is to repeat the formula three times, and thank heaven for that because even if we are late arriving, we still can hear the words: May they all be undone, repealed, canceled, voided, annulled.

Traditionally, the first time, one says the words softly, as one who hesitates to enter the ruler’s palace to make a request; the second, a little louder; and the third even louder, as one who is used to being in the ruler’s court.

Embellishing the courtly setting is the Torah pageantry. Before Kol Nidre is said, all of the congregation’s Torah scrolls are taken from the ark, and as an honor, presented to individuals to hold. In an unambiguous display, the staging lets us know under whose authority the court has been convened, and for good reason.

The Torah contains several verses concerning vows, and teaches that “you must fulfill what has crossed your lips and perform what you have voluntarily vowed to the Lord your God”(Deuteronomy 23:24). In so doing, it helps to explain the need and urgency for a legal formula that covers instances when we have messed up.

But for what year? Originally, the text read that the period the formula covered was from the “past Yom Kippur until this Yom Kippur.” However, according to “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Prayer,” Rabbeinu Tam (1100-1171), the grandson of the famous French Torah commentator Rashi, argued “’of what value is the cancellation of all vows to him who takes them and immediately declares them null and void?’”

He revised Kol Nidre to read “from this Yom Kippur to the next,” the text that most machzorim use today, although some Ashkenazi and Sephardic congregations use both, covering past and future. Others feel the revised text sufficient since it is ambiguous enough to cover the past and coming years.

For many Jews, the rush to hear Kol Nidre is not so much about the words as it is the music. Setting the table for a spiritual experience, and answering our emotional needs, if ever there were a song to begin a fast by, this would be it. Several variations are in use today, but most are derived from what is called a “Mi-Sinai” (from Sinai) melody — that is, according to Cantor Jonathan L. Friedmann, a tune “treated as if they came from Moses himself” — that emerged in Rhineland communities of Germany and France sometime between the 11th and 15th centuries.

Even if your singing voice is not one with the angels, or you can’t carry a tune in a bucket, you still can remember how some of Kol Nidre goes. Especially where it drops down low, then rises majestically, the music seems to imbue us with a sense of identity and a way to acknowledge our frailties.

The rush to shul has been worth it. Standing in the presence of Torah scrolls, family and friends, dressed in your best, maybe even in white, with the words and music washing over, we have arrived at that rare point in time when we can feel regret, and nullify some of our poor judgment.

Whether the formula gives us cover for the coming year or a chance to disavow past vows, we stand at a rare and powerful moment. Kol Nidre can lift us over missteps of the past year and help us to think, not twice but three times, before stepping into the new.

////\/\\\\

Closed bakery burns

Photo Michael Levin

The vacant building on Fairfax that once housed Diamond Bakery, unlike their once-popular challah and regelach, was burned to a crisp in a fire October 8. No injuries were reported.

The Bakery, which opened on Fairfax in 1946, and closed in December 2023, was known for its corn rye, raisin pumpernickel, and braided egg challah.

In the early 1970s, the bakery was owned by the Rubenstein family, Nathan (who died in 2002) and Ruth, and then their son, Steve. The Lottman family were also co-owners, during that period. Regulars will recall Ruth Rubenstein, or Gutka, a Holocaust Survivor, working behind the counter.

In its day, Diamond Bakery was the news center of the neighborhood. “If a shopper orders a fancy cake, everybody has to know whom the party is for; if someone wants more than the usual number of rolls, well, who’s coming for Sunday brunch,” said a 1977 article in the Los Angeles Times.

Diamond Bakery continues to produce baked goods at a facility in Montebello, available a various stores in Southern California.

////\/\\\\

Testing the flame

Edmon J. Rodman

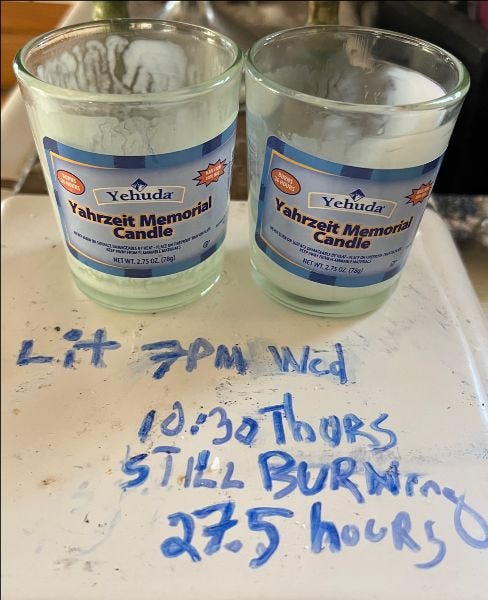

After a report from a friend that his Yehuda brand yahrzeit candle burned for fewer hours than the 26 stated on the label, I put them to a test.

My testing lab, would be a kitchen counter, and my test samples bought at Ralphs.

As the sun set on Wednesday, I had reason to light two candles, as it was both the yahrzeit of my Mother Pearl, and my Aunt Millie. Though their lights were very different, I would light the same candle for each. They were sisters, after all.

Would the memorial candles provide the flame for the promised time? Would they go the distance?

Lighting a yahrzeit candle is a custom that goes back to Talmudic times. The candle-lighting relates to a verse from the Book of Proverbs 20:27 "The human soul is the lamp of God."

In addition to lighting a candle for a loved one on the Hebrew anniversary of their death, it is customary to a light one on Jewish holidays when yizkor is observed, including Yom Kippur.

As I lit the candles, I tried to see my mother, who loved her kitchen, and my aunt, who was getting her life back together, when she died tragically in a car accident.

Thursday morning, the candles were still burning, and that night before going to bed, I went downstairs around 10:30 to check on them.

In the darkened kitchen, they were still burning. The only light, they illuminated nearby bags of half-finished challahs, the remains of a rye bread, and a memory or two.

The candles had passed the test, burning 27.5 hours, and still had several hours of light left in them.

Tonight, as the sun sets into Kol Nidre, I will take out more yahrzeit candles, and light a whole family of them.

////\/\\\\

GUIDE FOR THE JEWPLEXED:

Team Yom Kippur wears white

Edmon J. Rodman

These days, more people are wearing white after Labor Day, especially on Yom Kippur. Last year, to keep up with the trend, I looked to buy a white suit to wear during my yearly battle of spirituality vs somnambulism. I had heard that everyone else in my congregation was going to wear white, and on this day of communal confession, I wanted to be part of the crowd.

I also figured that on a day when God is supposed to take note of us as we pass before Him, Her, They (choose your Judge), it’s not a good day to stick out.

Why wear white and not the more traditionally somber black? After all, according to one interpretation, white is supposed to make us look like one of the angels. (I suppose that if the angels aren’t white as snow, as they are always depicted, at least they must look good in it.)

White is also a symbol of purity and repentance, and on the Days of Awe it’s what all the Torah scrolls are wearing.

White, it should also be remembered, is what many Jews are wearing when they are buried. The kittel, as it is called, is a kind of white robe-length shirt that many traditional Ashkenazi men wear on Yom Kippur. Wearing the kittel is meant to remind us of the gravity of a day in which we are struggling with life and death.

By those standards, my day shopping at Macy’s, where I had happened upon an after-Labor Day white sale, was very much in keeping with the spirit of the Day of Atonement.

Having looked up some shopping tips online, I found that when shopping for white, it was important to check for transparency. So when I found a pair of pants, I stuck my hand in them. Good thing I checked; I could see it waving at me. If I had bought them, on the holiest day of the year, more than my soul would be on review, and not just by God.

On a second rack, I found a less see-through pair, and they were a perfect fit.

“But are they going to fit on Yom Kippur?” asked Brenda, my wife and holy day fashion consultant who had come along to offer guidance.

She was right. I was on a diet, and by then, hopefully, would lose an inch or two. So I squeezed into the next smaller size, and did the same with the coat. So what if the suit cut off my circulation. If as it says in Isaiah “our sins shall be made as white as snow,” I would at least look like I tried to make amends.

For a lot of us, wearing white at anytime is a bad idea. It makes us look pale, sickly, or like Tom Wolfe. I know this day above all others is not about earthly style, but looking in the mirror on my way out to shul, I could barely believe my eyes. I didn’t look much like an angel; more like an angel’s milkman.

Perhaps white wasn't my uniform.

Years ago, when our children went to summer camp at Camp Alonim in the Simi Valley, here in California, we had to shop for white outfits for them to wear on Shabbat.

The camp’s dress code stated that the outfit had to be pure white. Not off white or kind of white, but blazing white — the thought being that when the teenagers came together on Shabbat for prayer, they would see themselves as a like-minded community. Kind of like a Shabbat uniform, I thought.

Except it wasn’t.

On a Shabbat when we were invited to visit, we wore white, too, but, surprisingly, the effect was beyond uniform. Each person wore white differently, and the effect, of a common fabric wrapped around the entire congregation, was like a shechinah in cotton and light.

It was a light that on the Kol Nidre I hoped to step into.

When adults wear the same color, they are often drawn together, but for reasons not apparently spiritual. For sports, we put on the team’s colors, sit in the stands and cheer. For war, we put on our country’s uniform and try to stay alive. On St. Patrick’s Day, even Jews wear green to fit in.

Is wearing white any different on Yom Kippur — a day of cheering for our side and trying to stay alive for another year, even if we do it just to fit in?

For a day, white on white are the team colors drawing us together. And even if we have a wine accident at the break fast, like I did, we still can start anew. That is, if you have one of those stain remover pens on you.

////\/\\\\

Moving High Holy Days

Are you searching for community?

The Movable Minyan, Los Angeles’ oldest independent, lay-led, and egalitarian Jewish prayer community, will be holding Yom Kippur services at the J, formerly the Westside Jewish Community Center.

This year, on Yom Kippur afternoon, the group will be discussing Rabbi Alan Lew’s thought-provoking book on understanding the High Holy Days “This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared.”

In our 36th anniversary year, the minyan’s services feature group singing, prayer and discussions, followed by a communal meal.

For more info click HERE.

////\/\\\\

Seen on the way: Pico-Robertson

Teki-yumm! When these shofar cookies are sounded, they call to your hunger for something sweet after a long day of fasting. These were found at Schwartz’s bakery on Pico, established in 1954.

////\/\\\\