Jewish Encampments

A New Scroll of LA Jewish News

Folks

Not every UCLA encampment has sought to deny Jewish history. In 2008, with the help of many children, I built my own encampment, a cardboard shtetl in front of Macgowan Hall. Organized by Community Arts Resources, and sponsored by Nextbook, the Jewish non-profit that would become Tablet, the shtetl used a hands-on approach to help participants understand, and even appreciate Jewish life in Yiddish-speaking eastern Europe. In the installation, as part of a day-long program called "Jewish Geography," there was a shul, market, several homes; even a couple of cardboard chickens. In today’s current UCLA atmosphere where some students and faculty deny Jewish history and spout antisemitic slogans, can you imagine this happening today? The shtetl, a historical model from Jewish communal life, that also existed in a climate of antisemitism, would be protested as “pre-Zionist,” or some such nonsense, and its builders blocked, or just cancelled. Who would even dare bring their children on campus for such an event? But, if I did redesign the cardboard shtetl for today's UCLA, I would make at least one historic correction—in the original I forgot to add cardboard Cossacks.

Speaking of cardboard…through MegilLA, I have broken out of the box of traditional Jewish Journalism, and I need your support to continue publishing. If you like what you read, if it makes you think, please support MegilLA with your paid subscriptions.

Shabbat shalom

Edmon J. Rodman

////\/\\\\

////\/\\\\

REVIEW

How Jews and Filipinos mixed and survived

Rudy's campsite bar mitzvah. Photo, Grettel Cortes Photography

Edmon J. Rodman

A mostly-overlooked real-life drama from the Holocaust that played out on the slopes of a holy mountain in The Philippines, has climbed to light in a new play. The premiere of “Mix-Mix The Filipino Adventures of a German Jewish Boy,” at The Los Angeles Theatre Center’s Playwrights’ Arena,” presents the story of how a bar mitzvah-age boy and his family survived WWII with the aid and friendship of the Filipino People.

Opening at a time when many LA Jews can feel a need for friendship and cross-cultural understanding, the play reminds us that “Yes,” when we have needed it, there are others in the world who have understood our plight, and were willing to help us.

In a city like LA that is populated by both Jews and Filipinos, along with an energized mix of ethnic cultures, the play, written by Boni B. Alvarez, and directed by Jon Lawrence Rivera (founding artistic director of Playwright's Arena), provides the audience with an historically-based guide for how people can survive by overcoming their differences.

Based on the WWII experiences of Ralph Preiss, now 93, the story was first presented here at a staged reading at the Skirball Cultural Center. “I am lucky I am still alive. Lucky that there were some good people around who helped us survive,” said Preiss, in an interview with MegilLA.

In the year he and his family escaped Germany, Preiss, as a child, began to understand why his family had to flee. “Boys were throwing stones at me and calling me ‘dirty Jew',” he said.

On stage, Ralph is the character Rudy Preissman, a displaced and questioning 13-year-old played with sensitivity by Casey J. Adler, making his debut with the Latino Theater Company, which is based at LATC.

In 1939, Preiss and his parents fled to the Philippine Commonwealth as part of a group of around 1300 Jews who were allowed entry through an “Open Door” program instituted by the country’s leader President Manuel Quezon.

When they arrived “It was very hot,” said Preiss. “It was winter in Germany when I left.” Before their clothes arrived the following month, all the young German had to wear were pairs of long pants.

Ralph Preiss in Germany. Preiss family photo

As to why Jews had been invited to the Philippines, Preiss in a Zoom talk given in 2020 observed that “Filipinos had been a conquered and persecuted people for much of their history and they identified with the Jews of Europe. In fact, one of the larger demonstrations against the crimes committed on Kristallnacht was held in Manila.”

In the play, Rudy and two Filipino friends serve as scouts for a group of Europeans and Filipinos escaping a Japanese army (and Germany ally) on the retreat from an advancing U.S. Army invasion force. Rudy’s family especially is in jeopardy since the Japanese have warned that for every one of their soldiers killed, 10 Europeans will be executed.

As the young scouts search the terrain of Mount Banahao for a spot suitable for a group encampment, they develop a new bond.

As remembered by Preiss, on these searches, “We were only talking about where to find food and how to survive,” he said. However, Alvarez, who was given the freedom to delve into this relationship, goes deeper.

Initially, to find relief from their awful circumstances, the two Filipinos, ask Rudy to tell them stories about his life in Germany; the movies he has seen, and especially his girlfriend.

As they grow more curious, they want to know why Jews had to leave their homes. They also are intrigued by the concept of Rudy’s upcoming bar mitzvah. We see that their understanding has evolved when one of them presents him with a yarmulke made of sewn together leaves to be used on the day he becomes a Jewish man.

Through the skill and research of the author, the mountain camp bar mitzvah moves beyond the perfunctory. Rudy, in a moving scene, chants haltingly from memory in Hebrew (A first for LA theater?) the final three verses from the Torah reading read on the Shabbat before Purim. It is in those verses that Jews are commanded to “Remember the Amalek,” a people who had viciously attacked Israel while they were tired and wandering in the desert. While on the mountain, fleeing from a more modern enemy, the Amalek are remembered.

Afterwards, the groups raise Rudy, as if on a chair, and they circle dance; a device the play’s choreographer Reggie Lee uses to show how the two cultures are moving together.

As the Japanese pursuit heated up, the destruction that Rudy and his friends witness from the heights shocks them, making the trio wonder if they will survive. As portrayed in a repeating flash back, Rudy has felt this way before, in Germany

On Kristallnacht “I was lone with my grandmother,” remembered Preiss. “Suddenly people started smashing out windows. Our grandmother woke me and we went to the attic to hide.” Fortunately, a neighbor who fired a warning shot caused the attackers to flee.

As the relationship between the scouts deepens, Rudy draws from their culture as well. As the three enjoy a Filipino concoction called Halo-Halo, or Mix-Mix, made with milk, sweetened beans and fruit, one of the scouts tells him that the dessert is like the three friends—the more they are mixed, the better they become.

To the extent we have forgotten about this positive blending of cultures during wartime, and during the Holocaust “Mix-Mix” helps us to remember. Along with remembering those who sought to destroy us, we need to remember who were are friends.

In our own city there is a statue remembering the bravery of Raoul Wallenberg a Swedish diplomat, and Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese official who each saved thousands of Jews. Though there is no Holocaust hero statue for Manuel Quezon, “Mix-Mix,” not only makes us recall his righteous act, but those of Filipinos who helped many Jews, including Ralph Preiss and his family, to survive.

Mix-Mix: The Filipino Adventures of a German Jewish Boy,” on stage at The Los Angeles Theatre Center May 18 to June 16, 2024. TICKETS HERE

////\/\\\\

* Live from the Archive:

Hammering away at war

Striking some provocative sparks for the Memorial Day weekend, is a powerful anti-war image by Jewish LA artist Saul Rabino. Titled “Prophecy of Isaiah,” this piece visualizes the well-known verse from the Book of Isaiah: “And they shall beat their swords into plowshares.”

In this signed lithograph from the late 1930s, drawn in a social-realistic style, the machinery of war and death hammered into the implements of farming by a resolute blacksmith. Topped by a rainbow, doves, and the word “Shalom,” this is a work meant to usher in the hopes of a war-weary world.

Saul Jacob Rabino (Rabinowitz), painter, muralist, printmaker, and sculptor, was born in Odessa, Russia on July 2, 1892. He studied at the Russian Imperial Art School and later in Paris at the École des Arts Decoratifs. From a family of rabbis, his Jewish education and religious feelings often shaped his art.

A 1946 piece in the B’nai B’rith Messenger described him as a tall man with a thick brown beard “On the younger side of middle age, and with an attitude and outlook as lithe as his step and manner…Something of his softness, and something of the old Hebraic prophet that is in his painting is in him.”

Rabino immigrated to the United States in 1922. In 1932, he moved to Los Angeles where he found work on the WPA Federal Art Project. In 1937, he painted the mural “Moses—Hebrew Prophets” for the Hebrew Shelter Home (Jewish Home for the Aged) in Boyle Heights.

Working under the WPA Graphic Art Division, he created lithographs of many subjects including chess players, music, entertainment, Jewish life.

During the 1940s, his attention turned to the war and the suffering of Jews in Eastern Europe.

In the early 1950s, he traveled to Israel to paint and exhibit his work, and to teach.

When he died in LA in 1969, he was remembered as a “man who translated all the pangs and joys of Jewish living into paintings.”

His work is represented in the permanent collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland; the Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, Minnesota; the Jewish Museum, New York; the Seattle Art Museum, Washington; and the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

For those interested in obtaining one of Rabino’s works, many fine examples can be found on eBay.

*The Rodman Archive of Los Angeles Jewish History is a collection of approximately 1000 objects, photos, clothing, art, books, recordings, and ephemera relating to the lives and endeavors of Jewish Angelenos between 1850 and 1980.

////\/\\\\

Seen on the way: Rancho Park

Kome, es bueno: borekas para todos! Eat, it’s good: borekas for everyone!—A Ladino phrase.

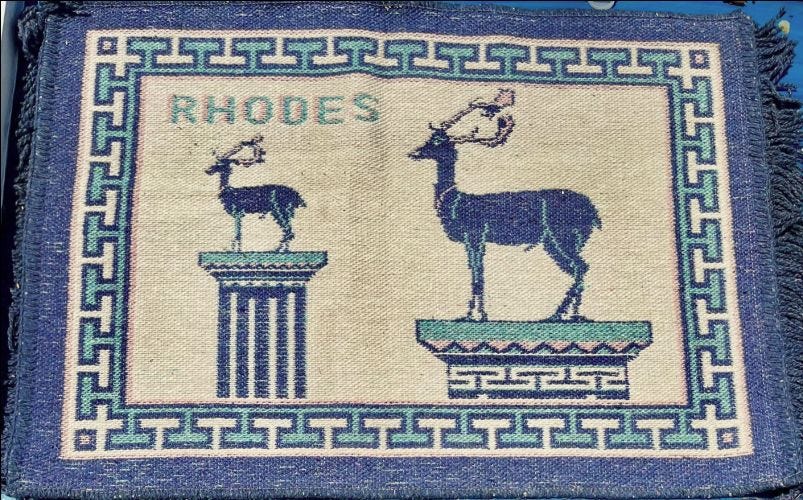

On a cool, but sunny Sunday, May 5, several generations of Jews whose families came to Los Angeles from the Island of Rhodes, gathered for the annual Rhodesli Family Brunch in Rancho Park. About 100 in number, from all over Southern California, and even Las Vegas and Oregon, they represented many of the Sephardic families who immigrated here from that tiny island in the middle of the Aegean Sea. Coming together for brunch, they enjoyed a Sephardic meal of borekas (pastry with a variety of fillings), boyos (spinach or cheese-filled round pastries), quijado (spinach quiche), pastelikos (meat pies), soutlach (rice pudding), ashuplados (meringue cookies), baklava (phyllo dough, filled with chopped nuts and soaked in syrup or honey) and, biscochos (ring-shaped crispy cookies), cooked with authenticity and joyously served by members of the community. While enjoying the spread, families were re-united, and a year’s worth of news caught up on. When one of the picnic organizers was asked “Why did you start doing this?” she replied: “We got tired of seeing each other only at funerals.”

////\/\\\\