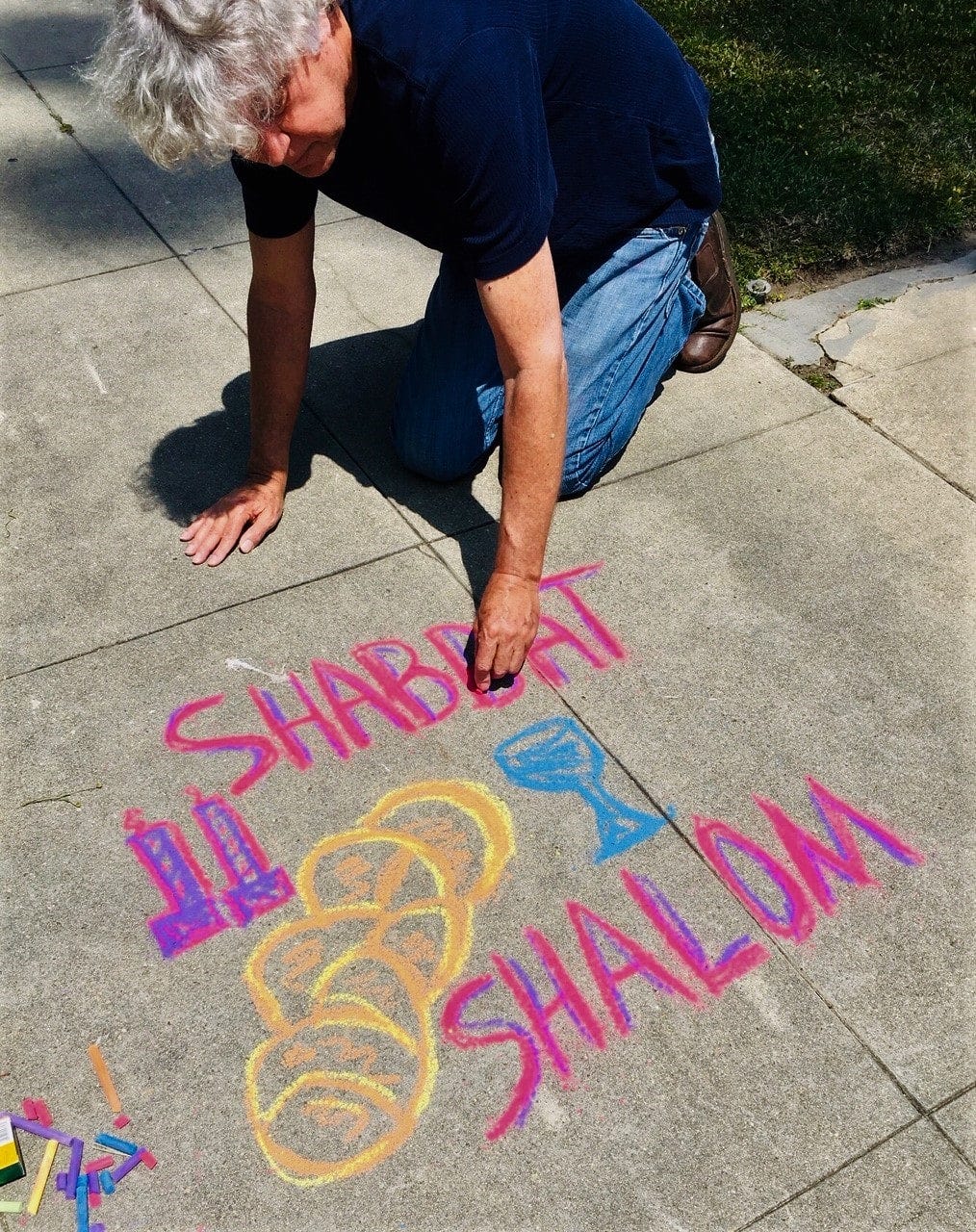

Cooped-up Angelenos are discovering they have sidewalks, and that they provide an excellent surface for communal expression. On Friday afternoon, with a little chalk, and an eye on the day of rest to come, I did a little expressing of my own in front of our house: Shabbat shalom with all the fixins'. In spite of the quarantine, and the time spent circling in your own steps, I hope you have had a fulfilling week. To help bring it to a thoughtful conclusion, I offer this week's edition of MegilLA.

Zay gezunt. Be well.

Edmon J. Rodman

When the Spanish Flu struck LA Jews

Edmon J. Rodman

Headstones in Mount Zion Cemetery, East Los Angeles.

Stuck at home in our 1916 house these last weeks, I began to wonder what my life would have been like if I had lived here during the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-19. Would I have been required to mostly stay at home? Would my kids be home from school? Could I go to shul?

The house is filled with windows facing the street, and on a sunny day when I had blacked-out the grim COVID-19 news, I imagined the people I saw pushing baby strollers, walking dogs, and riding bicycles all wearing outfits from the early 20th century. With the change in era, my neighbors looked nearly naked without earbuds.

The Spanish Influenza epidemic spread through the U.S. in three waves: from mid-March to mid-April in 1918, when it was most virulent in L.A.; from late August to mid-December; and from January 1919 until the middle of that year.

In those years when the city’s growth was booming, rising from 319,000 in 1910 to 576,000 in 1920, while the Jewish population of L.A. was estimated to be around 20,000 in 1917. Most of the Jewish community was still concentrated in the downtown area, or within a few miles of it.

My home, located just east of Western, near Pico, would have been just a short trolley car ride away from the Jewish restaurants, markets, shops and department stores located in the busy Broadway area. Would I still have been able to shop in them? A conservative Temple, Congregation Sinai had opened on Valencia St. in 1909, would the flu have closed it down?

Unlike today, in that outbreak, healthy young adults were considered more vulnerable than the elderly. According to 1922 U.S. Department of Commerce statistics, in 1918, 460,000 individuals between the ages of 20 and 39 died in the U.S. that year. The average number of deaths in that age cohort from 1900 until 1917 had been around 170,000. Of the 94 Angelenos who died in between October 17, and November 30 of 1918, 57 were between the ages of 20 and 40.

Had the Jewish community also suffered losses among its young adults?

I had already seen evidence of the grim results in the Jewish community. Last year during a visit to the small Mount Zion Cemetery in East Los Angeles, I noticed a large number of headstones of young men and women dated 1918 and 1919. Later I learned, from my own survey of cemetery markers, and from a survey of the cemetery done by the Jewish Genealogical Society of Los Angeles in 1995, that the vast majority of those interned in those years at Mount Zion were between the ages of 18 and 42.

But beyond the death totals, I wondered how the Jewish community had coped with that same fear of illness, and news of death, that hovers over us today.

On October 10 of 1918, with the number of cases rising, city and health officials met to decide on a course of action.

Opening my LA Times on October 11, 1918, I would have read that the Liberty Day parade scheduled for that day, organized to help sell war bonds, was cancelled, in order “to prevent the danger of spreading influenza by reason of crowds." More importantly, in that same piece it was reported that the city health commissioner “ordered that all schools, colleges, churches, theaters, motion picture houses, and all other places of amusement shall close and remain closed, from that evening “until further notice.”

Those found in violation of the law could be fined $500, and/or imprisoned up to six months.

“I hope and believe that it will not the necessary to keep the order in effect very long,” said Mayor Frederic T. Woodman, eerily presaging the unsupported optimism of some of our current leaders.

Many stores, besides those that sold food, were allowed to remain open.

The National Association of Motion-Picture Industries decided to discontinue all film releases on October 13, though not everyone in town agreed with that decision. Sid Grauman, manager of Grauman’s Theater told the Times, that “he had not heard a single sneeze in any of this audiences.”

Photo of Sid Grauman

A list of “may" and “may nots" was also issued by the city’s chief of police. “Mob scenes in movie work” were prohibited. Red Cross auxiliaries could continue to meet in churches. Pool halls were closed; football practices were not allowed. Courts and medical clinics would remain open. All funerals would be private.

Instructions from the State Department of Health advised that if you caught influenza “never cough or sneeze without covering your mouth with a handkerchief,” and “do not spit on the sidewalks.”

With all the churches and synagogues closed, the following Sunday, the Times under the headline “Go To Church In Your Own Home Today,” made its pages available for sermons. Avoiding the weekly Torah portion, or any talk of spirituality, Rabbi Edgar F. Magnin of Temple B’nai B’rith (today, Wilshire Boulevard Temple), used the opportunity to exhort the public to buy war bonds.

Even with the closures, by October 26, 55,000 cases had been reported statewide, and by November 23, the number had risen to 158,000. During that span, the Jewish community became more keenly aware of the deadly effects, and if I had been a reader of the B’nai B’rith Messenger, each week, I would have read the obituaries of those who had died from the Spanish Flu.

As today, I hoped not to see the name of someone I knew.

In my imaginings of that era, I had been attending a Conservative Synagogue nearby, Congregation Sinai; I liked the rabbi and the organ music. I was just getting to know a few of the congregants, when, near the end of November, I read in the Messenger an “In Memoriam” written by the congregation’s rabbi, Isidore Myers.

On November 20, Mr. and Mrs. Ellis Cohen’s son, Julian, had died from influenza, and the rabbi had written a poem:

Jewish in sentiment,

Under grief’s strain.

Let faith Omnipotent

In your souls reign!

As it is heaven-sent

Naught be the pain.

I also read that influenza had taken another congregation member, Mrs. Emma Kazinsky Loeb, wife of Adrain Loeb, the well-known wholesale produce merchant. “Mrs. Loeb struggled…for two weeks, and finally succumbed on Sunday,” said the story.

The Loeb’s had no children, but in the Jewish community, the Spanish influenza had “left many more orphans and half orphans than the war,” said John Kahn, the president of the Jewish Orphans Home of Southern California.

Though the Great War ended on November 11, the war against the pandemic continued. It was not until seven weeks after the ban on public meetings went into effect, that it was lifted on December 3. That night was the sixth night of Chanukah, and as I lit the menorah in the window, I would have been thinking about miracles.

Also in an upbeat mode was B’nai B’rith, which held an “In-Flu-En-Tial Meeting” to organize and celebrate on December 10—perhaps too soon.

In the first weeks of January, 1919, the messenger reported several more deaths in the Jewish community; among them, Ronnie Jaffa, age 34 He had worked for the family wholesale shoe business, and was thought of as “a man of integrity and high ideals,” and had "a host of friends to mourn his loss," said the Messenger. At his passing, he left behind Minnie his wife, who also caught influenza, but recovered. Rabbi Magnin officiated at the funeral, and Ronnie was buried at Home of Peace.

Though in the following weeks, the numbers of cases and deaths from the Spanish flu tapered off, it took months for synagogues to gradually return to their previous attendance. At that time Jewish Angelenos, if they chose, could recall another stanza of Rabbi Myers poetry:

Comfort knocks, pressing,

Open your hearts!

Heaven’s kind blessing,

Never departs.

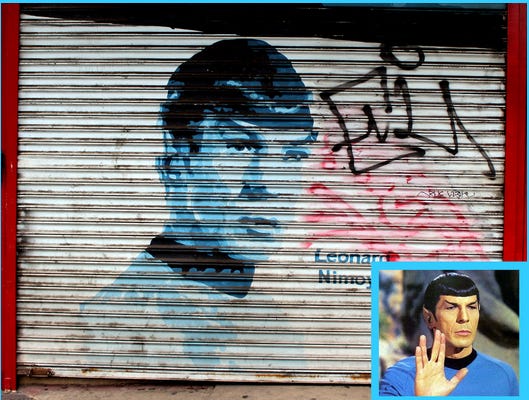

Torah on the Streets of LA

This week’s (5/9) Torah portion, Emor, “Speak” is all about the priesthood, the Kohanim. It begins with the special laws pertaining to the priests: They cannot come in contact with the dead of their clan, and they cannot shave their heads, or gash themselves. They cannot officiate in public if they have any physical defects. The high priest can only marry a virgin. Basically, they need to be strong, upstanding, holy guys, set apart from the rest. Thinking of a modern Los Angeles referent for all things Kohen, I need to go with the Star Trek character Spock and the Jewish actor who played him, Leonard Nimoy. Spock certainly lived by a higher standard, and his actions were guided by a kind of holiness of pure logic. Besides, who could have given a more lasting spin to the Kohanim than Leonard Nimoy (1931-2015). In the 1960s on Star Trek, he introduced the v-shaped parting of the fingers that a Kohen makes during the Birkat Kohanin as a Vulcan greeting. Where can you pay proper homage? On the northwest corner of Cherokee Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard you can find Nimoy’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Adding to the scene, directly behind, painted on the roll-up security door of a souvenir store, is an image of Nimoy as Spock. Live long and prosper.

Small museum and big hearts

Edmon J. Rodman

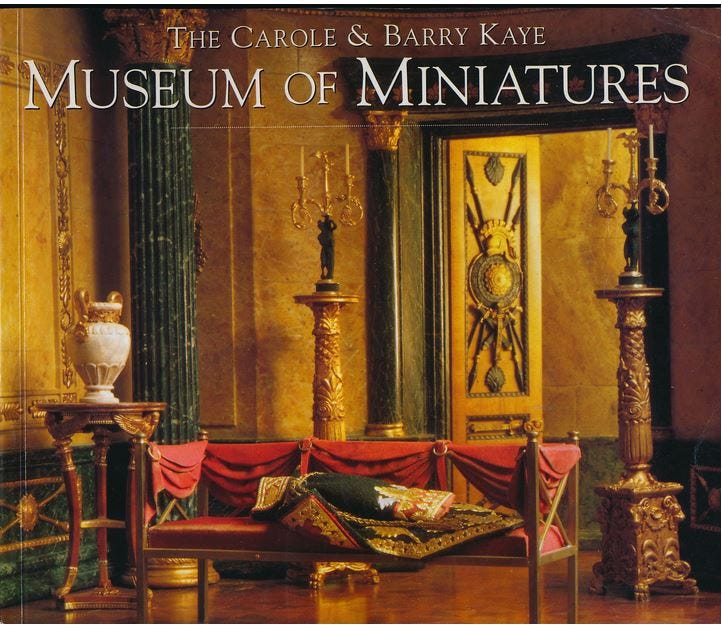

Both Carole and Barry Kaye, a Jewish couple who once opened a miniature museum on Wilshire Boulevard, died in April, less than a week apart from each other, after complications from COVID-19. Barry was 91, Carole, 87.

Before moving from Los Angeles to Florida in 2000, the couple were major donors to local Israel Bond campaigns and the City of Hope.

Barry created new ways to market Life Insurance, and wrote seven books on his financial ideas. During the 50s, he was a radio personality; one of the top jocks in the country. Carole, also a businessperson, was a world-class collector of miniatures.

In 1993, the Carole and Barry Kaye Museum of Miniatures opened in a building across from LACMA.

Their large collection which contained more than 200 separate exhibits, fit tightly into two floors and 14,000 square feet. The collection featured miniature replicas of many architectural landmarks, including Versailles Palace, and the Vatican, and locally, the Hollywood Bowl. Also on view was a scaled-down Titanic created from 75,000 toothpicks.

Carole’s interest in miniatures began when she helped to build a dollhouse with one of her grandsons. “It was something to do together, and we just got carried away when we saw some of the artistry that was out there,” she told the L.A. Times. After discovering that life was a small world after all, she began commissioning pieces “just to show some people what the world is like.” She liked to think of her miniatures as “the world in the palm of your hand.”

Before leaving town, the couple approached the county and city with a proposal to keep the museum open, however, no deal was reached, and the museum closed in 2000.

Many of the miniatures in her museum were created by local artists. Before LACMA opened an exhibit of Vincent van Gogh in 1999, Carole commissioned artist Paul Saltarelli to re-create some of the works in one-twelfth scale. “My banners were hanging before they were hanging across the street,” she joked.

Seen on the Way/Rampart Village

Some liked it hot, even at the turn of the 20th century. The former Bimini Hotel was built in 1904 across the street from the Bimini Hot Springs and baths. Located near Vermont and 2nd Street, the Turkish baths and pools were frequented by members of the L.A. Jewish community and used for group pool parties, group swims, and swim classes. The springs were discovered in 1900 as a result of oil drilling, and the water was a constant 104 degrees and flowed at a rate of 100 gallons per minute. The hot water was pumped through pipes to the hotel and used for therapeutic purposes. The water was also bottled and sold as either carbonated or plain. The baths closed in 1951, and the spa and pool buildings demolished in 1956. Today, the former hotel/sanatarium is a residential substance recovery center run by the Mary Lind Foundation.