Folks,

Tekiya! With a blast of the shofar at sundown on Monday, the holiest day of the Jewish year will end. What happens on the way to that resounding moment, and how it happens, when we are at home, will capture our thoughts in unexpected ways. Towards that new opportunity of introspection and turning, I hope this issue provides the place for you to think, cry, and laugh over our present state of affairs. May this year be better than the last.

Shabbat shalom.

G’mar chatimah tova.

May you all have a healthy, peaceful and fulfilling year.

Edmon J. Rodman

GUIDE FOR THE JEWPLEXED

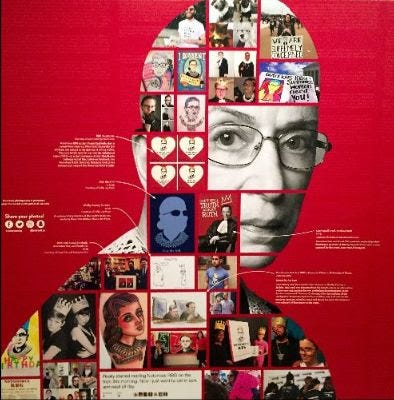

Is RBG a Tzadik?

Edmon J. Rodman

Within hours of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, the digital world was aglow with an obscure piece of Talmud. Just heartbeats after her passing, as the sun set into Rosh Hashanah, our phones were filled with the news that by dying on Rosh Hashanah, the late Justice had become a righteous person, a tzadik.

“A Jewish teaching says those who die just before the Jewish new year are the ones God has held back until the last moment bc they were needed most & were the most righteous,” National Public Radio’s legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg tweeted a bit after midnight.

Since Chanukah fell on Thanksgiving in 2013, I do not recall such a widespread Jewish buzz.

Of course, many of us had already thought of this Jewish fighter for equality in this way, but still, it was comforting, and revelatory to hear that Jewish tradition backed up our instincts.

Only, I had to wonder: Where did this idea come from?

Many of us have experienced a death in the family near this time of year. My mother, Pearl, died between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and amidst the grief, and the constraints of that period, frankly, there was no time to speculate on her future status in the vague concept of the afterlife.

But, now in a matter of hours, we were projecting RBG into an exalted place in Heaven. It’s a beautiful idea, but how did it come to us? From the Babylonian Talmud, if you must know.

Not that the text says someone who dies on the Jewish New Year is a holy person, but it does, create a path for that thought, as it says:

“It has been taught [Rosh Hashana 16b-17a]: Beit Shammai says, there will be three groups at the Day of Judgment — one of completely righteous, one of completely wicked, and one of intermediate.”

To break this down, it helps to know that Rosh Hashanah, besides being a day of apples and honey, is mainly considered to be the Day of Judgment, so RBG’s death on Rosh Hashanah, puts us in the right interpretive neighborhood.

The Talmud goes on to say that “The completely righteous are written and sealed immediately for everlasting life;” explaining why RBG or any other virtuous and justice-seeking person could be considered a tzadik.

And everyone else? “The completely wicked are written and sealed immediately for Gehinnom [Gehenna],” a kind of a hellish Jewish low place, and the “the intermediate will go down to Gehinnom and scream and rise again.”

Ouch.

The school of Hillel (thank heaven for Hillel) suggested a more forgiving view: The middle group are sent directly to Gan Eden (Heaven) instead of Gehinnom after they die.

As for God holding them back because people like RGB were needed most, the Talmud in our own hearts told us that.

Though a timely and beautiful thought, I am not sure if this Talmudic concept fits the recently departed Justice. Would someone who had spent their entire adult life working for equality argue against the higher status and special treatment, even if deserved? Would she wear her dissent collar in heaven?

Or would RGB be in Gehenna with the rest of us of “intermediates,” feeling a little burn from a lifetime of hard choices before we make our way to whatever place of rest it is we are going.

And the wicked? Especially those who seek to undo all of Justice Ginsburg’s earthly works? The Gemara, offers hope, even for them. Said Rabbi Yitzhak: “A person’s sentence is torn up on account of four types of actions. These are: Giving charity, crying out in prayer, a change of one’s name {to confuse the Angle of Death], and a change of one’s deeds for the better.”

Adhering to the letter of RBG’s final request would also qualify.

Torah on the Streets of LA

On the afternoon of Yom Kippur, we take a deep dive with the Prophet Jonah. In the Haftarah, God wants Jonah to go to the city of Nineveh to call the local citizenry out for “their wickedness, but the reluctant prophet is not having it. Though he plans to flee to Tarshish by sailing ship, the Lord casts “a mighty wind upon the sea,” to block his escape. Once the ship’s crew discovers Jonah is the cause of the tempest, they reluctantly cast him overboard. God sends “a huge fish” to swallow Jonah, and an ocean-full of songs, children’s books, and mythos about being swallowed by a whale is born. In normal times, being swallowed by a whale doesn’t seem high on anyone’s bucket list, but these are not normal times. Today, finding refuge in a nice quiet place, away from people and politics, seems like a dream vacation, even though your clothes would probably smell like herring gone bad. Remember, that once inside the whale, Jonah is able to contemplate his fate and even write a pretty fair prayer. On the streets of LA, if you would like to get a feel for this episode of biblical proportions, take a drive to the corner of Gower and Willoughby, where on the west side of Paramount Studios, in 1994, marine artist Robert Wyland painted a “Whaling Wall” of two enormous cetaceans. Staring up at the huge expanse of blue, on a hot, masked summer day, you may feel the urge to pray for a ladder.

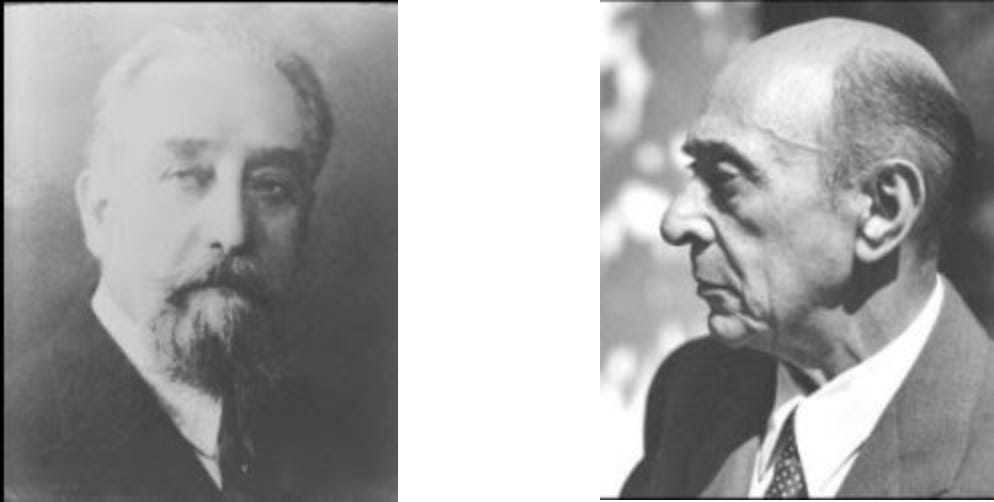

The Los Angeles Zimriyah Chorale performing Arnold Schoenberg's Kol Nidre, op. 39.

When Kol Nidre began with a burst of flame

Edmon J. Rodman

We like to think that the ideas enshrined in Kol Nidre, and especially its music, will always be with us. But in the late 1930s, in Los Angeles, there was a serious attempt to change the meaning, structure, and music of the age-old Aramaic legal formula that annuls the vows we have made before God.

To reinterpret Kol Nidre, Rabbi Jacob Sonderling (1878-1964), a highly-cultured, reform-minded German émigré, founder of a humanistic Society of Jewish-Culture Fairfax Temple, needed “a great master of our time” to take up the task, he wrote in an October 2, 1938 story for the Los Angeles Times.

For the creation of a new Kol Nidre, he looked outside the world of Jewish sacred music, and called upon another émigré living in L.A., Austrian-born Arnold Schoenberg, a composer, and musical theorist who shaped much of the world’s thinking about 20th century music.

Sonderling knew what he was up against. “The melody is old, known and cherished by all Jewry. Was there a possibility for a new interpretation? asked Sonderling in the L.A. Times.

In the freedom of Los Angeles, Sonderling had felt an urge to reshape and update Jewish liturgy and music to the needs of his time. During the rise of Hitler and fascism, he felt the story of Passover, “was no longer the story of Egypt and bondage, but the story of the titanic struggle today against bitter enslavement.” To express this struggle, he hired Ernst Toch, another modern composer who was living in LA, to compose “The Cantata of the Bitter Herbs.”

Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre (See a performance of it HERE) was also to be an original work, one that, wrote Neil W. Levin, for The Milken Archive of Jewish Music, “would resonate sufficiently in progressive circles as to be performable in the context of modern American Reform services.”

Yet, Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre, which included a poetic-dramatic speaking role for the rabbi, instead of a cantor or other soloist, orchestral accompaniment as well as a full chorus, would have been a musical bridge too far for most synagogues. That is if they didn’t have issues with Schoenberg’s critique of the original’s musical structure.

“After several months of study” of Kol Nidre, “Schoenberg has discovered a great many discrepancies of tonal structure as well as paradoxes between the melody and the words themselves,” began an article in the B’nai B’rith Messenger. “In his opinion, Kol Nidre, as sung, does not transmit the original effect” because of the “different attitude the modern listener takes towards the minor key.”

Schoenberg (1874-1951) was born Jewish, but left the faith for Lutheranism in 1898. In 1933, he returned to Judaism in an elaborate self-created ceremony in Paris. “During the period leading up to the Kol Nidre commission, Schoenberg became ever more fixated on an idiosyncratic brand of authoritarian, even militant Jewish nationalism,” wrote Levin.

A bearded Rabbi Jacob Sonderling, and Arnold Schoenberg

After his return to Judaism, he did a lot of thinking about the wording of Kol Nidre too.

“It was difficult for the average mind,” Schoenberg was quoted in the L.A. Times as saying, “to understand why the Jewish people should be permitted to make vows, oaths and promises and by reason of Kol Nidre consider them null and void. No sincere, honest man could understand such an attitude.”

Despite these sentiments, in the lyrics of Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre, the concept of annulling all vows figures prominently.

Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre, formally, Kol Nidre, op. 39,was scored for an orchestra of between ten and twenty pieces, a mixed chorus of 24 to 28 singers and a rabbi/speaker. In the work, it is the narrator who proclaims:

All vows, oaths, promises, and plights of any kind, wherewith we pledged ourselves counter to our inherited faith in God, Who is One, Everlasting, Unseen, Unfathomable, we declare these null and void.”

In the inclusion of this line, Schoenberg, perhaps, was influenced by his own recanted conversion. He was also painfully aware of his friends and other Jews still in Germany, and the addition “of plights of any kind,” could be seen to apply to things said for survival.

The opening narration of the work, which virtually explodes with a burst of kabbalistic and modernist light, must have come as a surprise, even to an audience expecting something very different from the premiere theorists of modern music. “At the beginning God said: "Let there be light!" Out of space a flame burst out. God crushed the light to atoms.”

Even this cosmic opening, however, is not without liturgical precedent as during the evening Kol Nidre service, the chanting of Kol Kidre is preceded by saying “Light is sown for the righteous.”

For the debut, Rabbi Sonderling spared no expense and rented the Fiesta Room of the Ambassador Hotel, the same ornate hall in which the Academy Awards were held in 1934.

To increase attendance, an ad was taken out in the B’nai B’rith Messenger which touted the service as including “New Ritual Music by World’s Greatest Living Composers.” (A piece by Ernst Toch was also part of the service.)

According to Levin, Schoenberg conducted on Yom Kippur eve services and Rabbi Sonderling narrated the script. One can only surmise the congregation’s initial response, as there does not seem to be any reporting on the Kol Nidre’s first performance.

At the very least, those in attendance knew, in a time of rising darkness, they were in for a night of vow-lifting lightness and light.

Yom Kippur is a day of remembering, and in a new video we can recall the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918, and see how it impacted the L.A.’s Jewish community. “We Remember,” based on an article that originally appeared in MegilLA, helps the viewer see new connections between our time of COVID-19 and the deadly pandemic which struck the city over one hundred years ago. The 4.5 minute short, with music by Craig Taubman, was written and narrated by Edmon J. Rodman. Produced by Pico Union Project, the video will be shown on Yom Kippur. Through its imagery and story, we find we are not alone. Watch it HERE.

Who will survive a Zoom YK?

Edmon J. Rodman

Zoom Yom Kippur is upon us, and we must know: Who will be fine while watching Yom Kippur services at home? And who will not? Who will be successful in making it till the shofar sounds at sundown, and who will succumb to max shpilkes?

Usually all we need to ponder is who will perish by thirst, hunger, plague earthquake. But this year, considering the circumstances, we also want to know:

Who will have their Internet crash, and who will log on with ease.

Who will be muted, and who will find harmony.

Who will be distracted by surrounding objects, and who will sit serenely in designer digs.

Who will need a lock on their refrigerator door, and who will sneak peeks at online photos of brisket.

Who will forget to remove their, umm, “play-time toys” from their background, and who will sit in front of a shelf of nicely curated books.

Who will wear clothing that matches their digital background, so that part of them vanishes, and who will look heavenly in white, even if only dressed from the waist up.

Who will spend the day sitting in shadow, and who will be bathed in the perfect on-screen light.

Who will repent in air-conditioning, and who feel the heat.

Who will have a day of digital tranquility, and who will be plagued by a barking dog.

Who will have food for a break-fast, and who will only have frozen home-made banana bread.

But there is hope: T’shuvah, T’fila, and Biden have the power to avert the severe decree.

Seen on the Way/ Sepulveda Pass

On Friday, the Skirball Cultural Center provided space on its front steps for a public RBG memorial. People, one woman even on crutches, brought flowers, photos, a crown, and handwritten notes. Among the display was a framed photo with RBG's famous quote '"I ask no favor for my sex...All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks."