MegilLA: Throwback Passover Edition

Saturday, March 27, 2021

Folks,

While searching my house for chametz with candle, feather and spoon, I found that the leaven had taken a year-specific form. Ending this terrible year of plague and wonders, I needed to adapt a ritual to cleanse my home and head. The next morning, I burned my findings in the fireplace as I said: Be gone as if you no longer existed! Return to the dust of the earth! In this season of renewal, when we remember where we came from, and how we got here, whether we sit together at the seder table, or not, we can move beyond the worst, and begin again to think about beginning; about the spring.

Can you help me to begin again? In a year of increasing freedom, there will be so much happening, and I want to continue to bring my reports to you. Does the sea have to part before you support this publication? Push the SUBSCRIBE button below.

Shabbat shalom. Chag Sameah.

Edmon J. Rodman

The Forward recently published a story by Louis Keene about Substack and the future of Jewish media, and MegilLA was included! Read it HERE

DURING PROHIBITION

How Bootlegger rabbis filled seder cups

Edmon J. Rodman

The Passover Haggadah calls for four cups of wine at the seder, but in the days of Prohibition, when you needed a permit to fulfill the requirement, what were your options? Would you use grape juice instead? Look for wine-less choroset recipes? Leave an IOU in Elijah’s cup?

Today, in a Kosher grocery store, or even Ralphs, the Jewish consumer, shopping for Passover, is confronted with a wall of wine bottles from which to choose: white, red, sweet, dry, domestic, imported from Israel or Italy, high priced, or cheap.

But during the years of Prohibition, from 1920-1933, in Los Angeles, like the rest of California and the U.S., such a luxury of choices was unheard of, and even if you wanted to legally obtain wine for your seder, you needed to find a rabbi.

After the passage of the 18th Amendment, which created a federal ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of Alcoholic beverages, enabling legislation passed by Congress, known as the Volstead Act, established the rules for sticking the cork inside America’s bottle.

There was a leak, however. In Title II, section 6 , there was an exception which stated that a rabbi, or other denominational religious leader could “supervise the manufacture of wine used for the purposes and rites.”

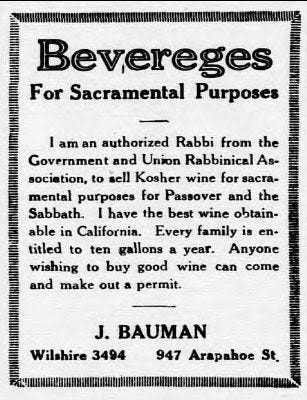

As early as 1920, moving to serve Orthodox as well as other Jews who wanted wine on their seder tables, was Rabbi Jacob Bauman (1871-1940). Serving as the rabbi of Congregation Talmud Torah (and later, Agudah Achim), he announced in an ad in the B’nai B’rith Messenger that he was authorized to sell “Kosher wine for sacramental purposes for Passover and the Sabbath.” Every family was “entitled to 10 gallons a year,” (later “reduced” to 2 gallons per family member) said the ad, and all they needed to do was “come by and make out a permit.”

That same year, trouble was already starting to brew with the permit process. A frontpage statement in the B’nai B’rith Messenger from B’nai B’rith Lodge 487 and the Jewish Community Committee of Los Angeles noted “that under cover of the Jewish name and religion, provisions of the Volstead Act have been violated in spirit, if not in letter, by a number of persons, Jewish and gentile, who have been purchasing wine for pretended sacramental purposes.”

“Incensed,” the writers of the statement called for “strict enforcement.”

The issue also bubbled to the surface in the Los Angeles Times. In October 1921, a story titled “Churchman is Held in Wine Case,” reported the alleged Volstead Act violations of Rabbi W. L Goldberg, of Congregation Ahavata Achim. According to the report, two women, “one professing to be a Jewess, obtained a gallon of wine” from the rabbi’s wife for $14. “Mrs. Goldberg was immediately arrested and taken to jail, and when her husband called to see her he was arrested,” said the story.

Rabbi Goldberg did have a permit, explained the story, but “the wine is to be used for sacramental purposes, and according to the regulations, may not be sold.” However, if a contribution "to the church” had been asked for, that would have been allowed.

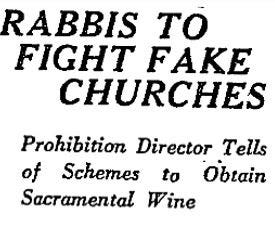

Another story in the Times “Rabbi to Fight Fake Churches,” in August of 1922, reported that S. F. Rutter, prohibition director of California, had called a group of L.A. rabbis together at the department’s local enforcement office to ask for their help in “running down the fakes who are posing as nebulous heads of mythical churches, and constantly violating the national prohibition law.”

“Unprincipled individuals posing as rabbis,” had organized “alleged churches” to obtain a “quantity of wine for supposed sacramental purposes, under the law,” said the article, “only to have stuff sold at an exorbitant price—all under the cloak of the law and the Jewish religion.”

In 1923, with all the evidence of rabbi “bootlegging” and the embarrassment it was causing to the Jewish community, the city’s leading Orthodox congregation, Beth Israel, “abrogated” their wine privilege.

By March 1924, after three years of abuse, California Prohibition director Rudder had seen enough. Since 1921, 21 rabbis had been denied further wine privileges, and ten rabbis had been arrested in Oakland and San Francisco. Not surprisingly, he suspended further issuance of permits to rabbis.

By February 1925, the state’s Jewish community had suffered enough from the “bootlegger” rabbis as well, and supported the introduction of a bill by Assemblyman Edgar C. Levey, which required rabbis to obtain certification from the district attorney, and from a prohibition officer before they could secure a permit to sell sacramental wine to members of their congregation.

In May of that year, pushing the cork back in, for awhile, the bill became law.

Torah on the Streets of LA

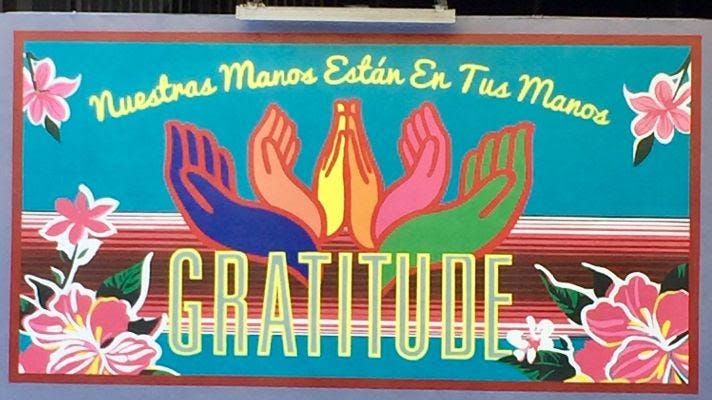

This week’s Torah portion, Tzav, is all about sacrifice. It’s an area, in which, this last year, we have all gained experience. In the reading, the Torah tells us there is a burnt offering for purification, and there is another to make reparation. There is also one for well-being. It can be offered for thanksgiving (for todah), after one has been spared from all manner of disaster. It’s an offering of profound gratitude and cosmic relief of having dodged the bullet. If you have just had your second COVID-19 vaccine shot, or, even your first, you may know the feeling. Though we no longer sacrifice animals, a handy and easy enough blessing called Birchat HaGomel (saying it is often referred to as benching gomel) offers an opportunity for expressing gratitude for having been spared. The blessing usually said when one has survived a life-threatening situation, like giving birth, a hospitalization or car accident. is said in the presence of a minyan, even on Zoom. Having a Torah present, though not absolutely required, is good too, so you can be called up for an Aliyah and Torah blessing. Here is a translation of what you say: Blessed are You, Lord our God, ruler of the world, who rewards the undeserving with goodness, and who has rewarded me with goodness.” After saying the blessing, the minyan, in solidarity, responds “May the one who rewarded you with all goodness reward you with all goodness forever.” While we are feeling gracious, we can check out the new Gratitude mural on the east side of the Mexico General Consul building in the Westlake area at 2401 W. Sixth St. Dedicated to all the essential workers who have helped pull us through the last year, the mural reads “Our hands are in your hands.”

(Note: If after your shot(s) you would like to bench Gomel and do not have a place, contact me though MegilLA.)

Come share a throwback Passover

Edmon J. Rodman

A throwback Passover requires a few key artifacts to open the gates of memory. But growing up, and even in adulthood, how many of us have stopped to take a picture of our seders? What we do have to remind of seders past are wine-stained haggadas, with seder-leader notes tucked between the pages. Expanding beyond that, there remain, in some quarters, the Passover children’s books, art, ephemera and objects that once animated our holidays. Join us as we unpack a few:

In “Seder Night,” painted by New York artist Raisa Robbins in 1947, a family rises to welcome the Prophet Elijah. Note his ghostly image in the doorway. Angelenos had two chances to see the piece when in 1949 it came to LA as part of a traveling show presented by the Art Center for the Congress of Jewish Culture in New York. (They also produced lithographed copies Robbins’ painting.) There were Jewish community-based neighborhood art galleries then, and you could see it along with 32 other works at the Sarah Singer Memorial Gallery of the Beverly-Fairfax Jewish Community Center, or at the Soto-Michigan Jewish Community Center in Boyle Heights.

There is no requirement for special Passover seder candles, but in the 60s, when marketers were looking for ways to extend their Jewish product lines for a generation which was beginning to re-discover their Jewish roots, why not package a blue and white pair?

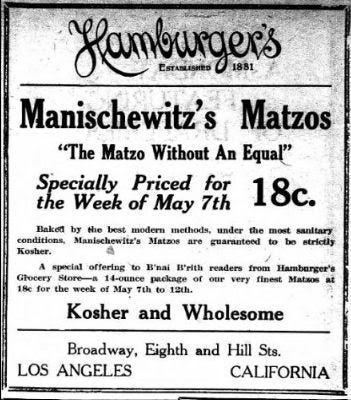

Hamburger’s was an enormous downtown store of many departments. (The building remains, and will eventually re-open as a multi-use building.) Along with all the usual clothing and furniture areas, there was an area for dental care, and for a manicure. The store also had a drugstore, a grocery store, and for a few years, the Central Library. Owned by the Jewish and community-minded Hamburger family, the store was the first large store to run specific newspaper advertising for Chanukah. The matzos ad, which ran in 1921in the B’nai B’rith Messenger, presented a product that was “Kosher and Wholesome,” and on special.

“There is much beauty and rich tradition,” wrote cookbook author Vivian Stone, in the introduction to “Passover Treasures,” published in 1975. From “seder dish to the kneidlach and sponge cake,” her recipes were presented to help the “Malkah, the queen" of the house, prepare the “most sumptuous feast of the year.” Vivian, who was married to Rabbi Samuel Stone of Temple B’nai Emet of Montebello, puts her dessert recipes like “Passover Fudge Cake,” and “Banana Cake” first, which is just where they belong.

Why is this grocery bag different? It presents a clever and everyday life 1990s approach to Jewish community outreach. The internet and social media have superseded all this, but then, with a simple pen, a shopper could contribute to helping disabled youngsters, and fostering “a sense of common Jewish purpose,” all while buying their wine, matzah and gefilte fish.

Do we long for the days of “Pesah is Here”? Published in 1956 it presents a seder story of a neat and tidy Jewish nuclear family; even the family cat dresses up for the seder. But even here, the winds of change blow: both son and daughter recite the four questions. This copy was once available through the Peter M. Kahn Jewish Community Library; a valued community organization long checked out.

Turning to art to tell the story of Passover

In a blog post, The Getty museum’s antiquities curator, David Saunders shares his ideas about how the museum’s collection can provide some visual inspiration for the stories people will tell at the seder and beyond. A wonderful visual and observational aid for your seder. Find it HERE.

Seen on the Way/ South LA

Waiting in the car line for my first COVID-19 vaccine shot was like the night before our ancestors left Egypt. The plague of death was in the air, and I was anxious and a bit in awe of what was about to happen. After checking me in, an official marked my windshield with a fat red marker. Like splashing lamb’s blood on an ancient doorway to keep out death, the red streak made me ask: Would it work? Rolling slowly towards my first shot, with the geodesic Faithdome in view, I knew that even after the passage of thousands of Passovers, I still needed hope, and to believe that protection was coming.