Shofar So Good

A New Scroll of LA Jewish News

Folks,

That sweet New Year that we all want, this is where it comes from. Several years ago, not content with the bear-shaped squeeze bottle of honey I found in the grocery store, I went in search of a new source, and found a Hasidic beekeeper out in the San Fernando Valley. His honey, to my surprise, was sweeter and his story fascinating. Our traditions, if we let them, can lead us to a wonderful exploration of the Jewish life around us both now and in the past. It is that journey of Jewish exploration that I can help you have in the coming New Year. It is my hope and design that MegilLA can help you on your path to a more engaging and enlivened New Year. But I need your help. This is my High Holy Day appeal: Please support this publication with your subscription.

Shabbat shalom.

Have a Sweet New Year.

Edmon J. Rodman

////\/\\\\

////\/\\\\

GUIDE FOR THE JEWPLEXED

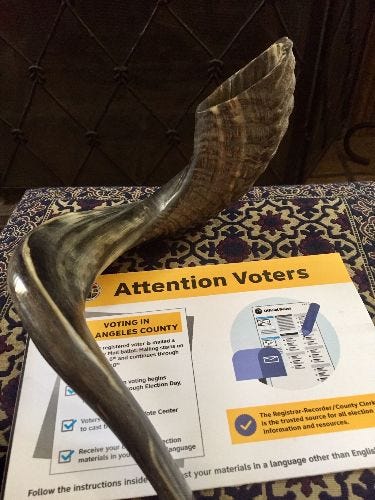

What the shofar reveals

about our politics

Edmon J. Rodman

In the High Holy Day season, which for many Jews marks the time when we begin to decide for whom and for what we intend to vote, the pollsters are asking the wrong question. To discover the leanings of Jewish voters, the question may not be the prosaic “who do you plan to vote for?” but the more aurally attuned, “what do you hear when the shofar sounds?”

As we stand each year at Rosh Hashanah for the sounding of the shofar, our heads fill with the sharp tekiyahs and shrill shevarims, awakening us to the possibilities of a New Year. With each sound, our hopes rise for a sweet new year: one filled with good health, happiness and peace. But, in the internal rhythms of those sounds, mixing with the static of an election season, we may also hear a voice asking: Who do I feel can best bring these auspicious things about?

Turns out, we each hear different things in music; a song that stirs you awake may cause your friend to snooze. “Different people really do sometimes hear the same sounds in entirely different ways,” reports Knowledge Nuts, an information website. “Even the smallest differences in our individual skull structure or bone density can change the way our brain receives and processes sound waves, changing the frequency that our bones vibrate at as we hear sounds.”

Perhaps as a result of those built-in differences, though we stand together to hear the shofar’s call, some people may hear a warning, and call to arms in the blasts, and others may hear an affirmation and a call to justice.

In the nine staccato blasts of the teruah, some may hear in the predictable pattern reinforcement of their belief that things must remain the same, while in the same sounds others may hear a cry for increased social change, with the result that each listener ultimately tunes in to the song of a different candidate.

How we hear the three medium blasts of the shevarim can also reveal much. Do they sound that we live in a society of growing financial inequalities? Or trumpet that we need to be unfettered to earn even more? Do we hear in them that we need to welcome the stranger? Or, that the stranger has become too strange for our comfort?

When hearing the final, long blast, the tekiyah gedolah, one might hear in those seconds of soul-stirring resonance the breaking down of walls, and racial barriers, another, taking in the same sound, may hear in the vibrations, a layered sound protectively rising. And what about those who only hear an extended drone? Perhaps they have yet to face the music, and are undecided.

More effective than any campaign commercial or candidate pitch, hearing the shofar can also have the power to change us by opening our minds. Even if we see the shofar spiraling to the left, or the right, could a ram’s horn also have the power to cut through all the political noise and change our presumptions, and even our vote?

“The shofar – a primitive instrument that to a stranger sounds like a lot of noise – has a magical power,” wrote Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis of blessed memory, a religious leader and inspirational speaker, “It is capable of penetrating even the most dormant hearts and souls,” she wrote, in her own way, campaigning for us to listen carefully to our own hearts and even to those of the people standing nearby.

////\/\\\\

The shofar's first sound in LA

A two-story adobe owned by John Temple where Los Angeles High Holy Day services were held. Illustration courtesy Water and Power Assoicates

Edmon J. Rodman

When was the shofar first blown in Los Angeles?

Few rituals connect us to our ancient past like the sounding of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah. As we rise to hear the tekiyahs, and feel their vibrancy, we can imagine our ancestors, thousands of years ago being stirred by the same sound; simple, pure and unamplified. But when we try to connect those sounds to our more recent past, in our own geography, we draw a blank.

To what time should we let our imaginations travel to hear and connect with that first sounding of the horn? Should we return to the years following WWII, when Jewish G.I.’s and their families moved here by the thousands? Do we need to go back further, to the era of the 1930s and the Great Depression? No, further still. to the gas light days just before the turn to the 20th Century? Not there yet. In fact, you would need to set the controls of your ‘time machine’ to decades before H.G. Wells published the book of that title in 1895, to come to a time when the first tekiyah was heard in L.A.

Our journey to the first shofar takes us to 1850. In that year, the first U.S. Census was taken in Los Angeles, revealing, in a total of 1,610 inhabitants, eight of whom were recognizably Jewish. If those eight came together to hold a High Holy Day service and blow the shofar— they could have invited others who lived in the region to reach 10 for a minyan or prayer quorum— there is no record.

But the shofar was coming.

Based on a report from Marco Newmark, one of the sons of business pioneer Harris Newmark, Max Vorspan and Lloyd P. Gartner in “History of the Jews of Los Angeles,” with more than a little doubt, say that “Jewish religious services are believed to have begun some time in 1851 when the first minyan was held.” It is entirely possible that the shofar in LA was first blown then, but there is no written account.

It was not until two years later, in 1853, when Joseph Newmark, a trained shochet (ritual slaughterer), who had started a congregation in New York and San Francisco and served as president of a third in St. Louis, arrived in Los Angeles, that Jewish life began to organize and started becoming more publicly known.

In 1854, Newmark organized the Hebrew Benevolent Society, and in that same year, Vorspan and Gartner report that religious services were also “formally organized” in L.A. We could assume those services included High Holy Days and a shofer sounding, but still there is no record.

Searching for a printed public confirmation of that first shofar blow, the September 15, 1855 issue of the Los Angles Star tantalizingly reported that “Our Israelite citizens the past two days, have celebrated the New Year.” Though the short piece noted that the “anniversary was observed in an appropriate manner; their stores closed and all business transactions suspended and services applicable to the occasion,” were held,” there is no specific mention of the shofar. It seems likely, though, that 1855 was the first year.

In the following year, however, we have solid evidence. The October 11, 1856 edition of the L.A. Star reported not only had there been a celebration of the New Year 5617, and presumably a shofar blowing, but a few days later, on October 9, Jewish people celebrated “The feast of propitiation called ‘kipoor.’” The paper reported that “the whole congregation went to synagogue, and continued there till evening, when upon appearance of the stars, a horn was sounded.” So, for the written record, there it is: October 9, 1856, for the first shofar.

As for where the shofar was sounded, the story also reported that “The services on Wednesday evening and Thursday last were held in the Masonic Hall,” not surprising since many Jewish pioneers were affiliated with the order.

Masonic Lodge, No. 42 began in 1853, and according to several sources, before building their own place in 1858, met in a two-story adobe owned by John Temple, at the intersection of Spring, Main and Temple, which became known as Temple Block, a site where L.A. City Hall is today.

What happened after the shofar was blown that day? As the L.A.Star reported, much like today, before returning to their homes, members of the congregation saluted “each other with wishes for health and prosperity.”

////\/\\\\

Torah on the Streets of LA

On the Shabbat before Rosh Hashanah, in the Torah reading Nitzavim, “You stand this day,” Moses exhorts Israel to “Choose life.”Addressing all of Israel, “from woodchopper to water drawer, he reaffirms the Covenant that was created between God and Israel at Mount Sinai. Moses affirms that God’s commandments and laws, “this Instruction,” is “not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach.” At a time when we are considering our own prospects for a New Year, the Torah Reading sets before us vastly different potential outcomes. “I have put before you life and death, blessing and curse. Choose life—if you and your offspring would live,” says Moses. Is the Torah simply asking us to choose life over death? Or, is it asking us to weigh our choices, directing us toward those who make a happy and healthy life possible? In matters of our physical beings, there are many in the field of medicine whose life choices have increased our own options to literally choose life. Commemorating some of those contributions, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center there is a large mural depicting some of the important contributions of Jews and Jewish law to modern medicine. Painted in 1999 by Terry Schoonhoven, and mounted on a wall in the Harvey Morse Auditorium (South Tower Plaza level, accessible when the room is not in use), the 12 by 71 foot mural presents 4000 years of medical history. There’s a film too (Watch it HERE) which takes you through the entire mural. Connecting us to the Torah portion is Moses holding a staff entwined with a copper serpent, the forerunner of the modern caduceus. Beyond Freud and Jonas Salk, are: Maimonides, a revered Torah scholar and physician; Isaac Hays, founder of the American Medical Association; Nobel Prize Winner, Gertrude B. Elion, who developed medicines to treat leukemia, gout and herpes, and whose work helped to develop AZT for the treatment of AIDS; and bearded Noble Prize winner Elie Metchnikoff who popularized yoghurt as a health food, and many more. Choose life, indeed.

Photo Michael Levin

////\/\\\\

Seen on the Way 1948:

The California Jewish Voice

Synagogues have been trying to fill High Holy Day seats seemingly forever. As indicated by this 1948 ad for the Breed Street Shul in the California Jewish Voice. One tried-and-true approach has been to promote the cantor. Not shy about pouring on the superlatives, the shul touts Cantor Israel Reich, a well-known tenor who sang in Hebrew and Yiddish, as the “Finest Cantor in America.” Throw in a well-trained choir, and even the most somnambulant congregant could be put on the path to a gud yontif and a happy New Year.

////\/\\\\